Project

Interview with Shinobu Soejima

2023.Feb. 3 (Fri) - Mar.5 (Sun)

Shinobu Soejima, who is participating in the current exhibition "Dystopia: Transition from Memory," is a remarkable artist who creates three-dimensional animated videos on the theme of the relationship between matter and spirit. After specializing in Sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Arts, University of Collage London, she graduated from the Tokyo University of the Arts' Department of Advanced Art and Design in 2018 and is currently elaborating her study in the doctoral program of the school's Graduate School of Film and New Media. Having spent his teenage years in Malaysia, Soejima researches Asian folklore, ethnic cultures, and the tactile qualities unique to each cultural sphere, in an attempt to examine and express the emergence of a sense of life in non-living entities.

In the past few years, she has received the Kimura Eriko Prize at the Art Award Tokyo Marunouchi in 2018, the Special Mention by the ecumenical jury at the 68th International Film Festival Oberhausen in 2022, and his representative work "Blink in the Desert" was screened at the Yebisu Film Festival (2022), etc. In the past few years, he has participated in numerous film festivals in Japan and abroad.

| Date | 2023.Feb. 3 (Fri) - Mar.5 (Sun) |

|---|---|

| Exhibition | Dystopia: Transition from Memory https://x.gd/In8Br |

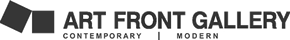

S. Soejima: "The Spirits of Cairn" has been shown at the Yebisu Film Festival in the past, but it was not exhibited together with the dolls, so this is a rare opportunity.

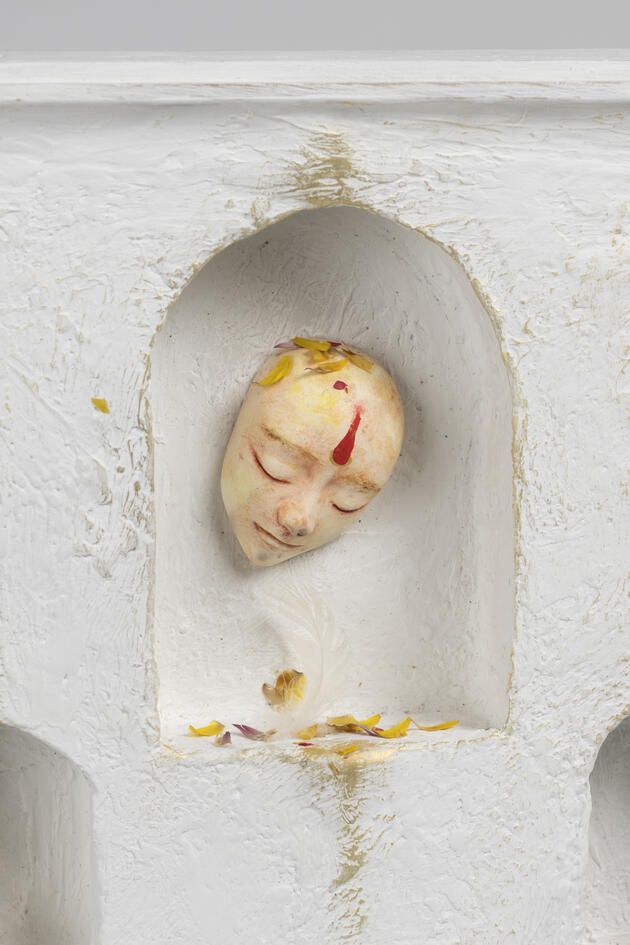

The Spirits of Cairn is the first three-dimensional animation I made in 2018. It is a narrative video work based on the motif of the afterlife where children who die young may end up. It is not a simple place like heaven or hell, but a place one step before death, like purgatory in Christianity or Sai no Kawara in Japan, that exists in various religions and cultures. It is a work that depicts a person wandering in a state of limbo, so to speak.

The main character, who is wandering around in search of his true identity, repeatedly mourns the so-called spirits he discovers and the things that symbolize death, one by one, in an endless process. I hope you will pay close attention to the story.

S: For example, the doll's facial expression seems to change between the beginning and the end of this work. I think my originality lies in the fact that the doll's expression changes as if it has experienced the time axis of this world by accumulating these "stains" and "breakages. So, while using the image of traditional dolls, I would like to try something new.

The word "cairn" means "masonry," and in places like Bihar, where there are masonry piles in the mountains, they sometimes mean graves, so I took the name "cairn" from there. So I took the word "cairn" from there, which is overlapped with the image of many bird heads and the masonry of the riverbank

G:Bird heads, insects, and other real creatures often appear in your videos.

S:Generally, animation in stereoscopic animation is an art of illusion that makes a material look like a living organism, and makes it look as if it is alive by moving it little by little in time-lapse photography, taking pictures of it, and playing it back in serial numbers. On the other hand, by incorporating natural objects into my three-dimensional animations, I also incorporate spontaneous movements of materials that I, the artist, cannot control, such as shape changes and deterioration over time during filming, as animations unique to three-dimensional animation. Normally, natural materials, whose shape is difficult to maintain during filming and whose movement is difficult to control, tend to be avoided because of the risk of losing the connection between frames and between cuts. At the same time, I believe that the tactile qualities of the material, such as hardness, fragility, and stickiness, can influence the narrative. In "The Cairn Heads," I included the head of a real creature to symbolize an invisible spirit, and the process of the soft raw flesh gradually decomposing during filming, drying out and discoloring the skin, was itself incorporated into the storytelling of this work, which is based on the motif of death. I believe that bringing such natural objects into contact with artificially created dolls in the film can create a sense of flesh and blood even inside inanimate dolls and produce a sense of life even for non-living objects.

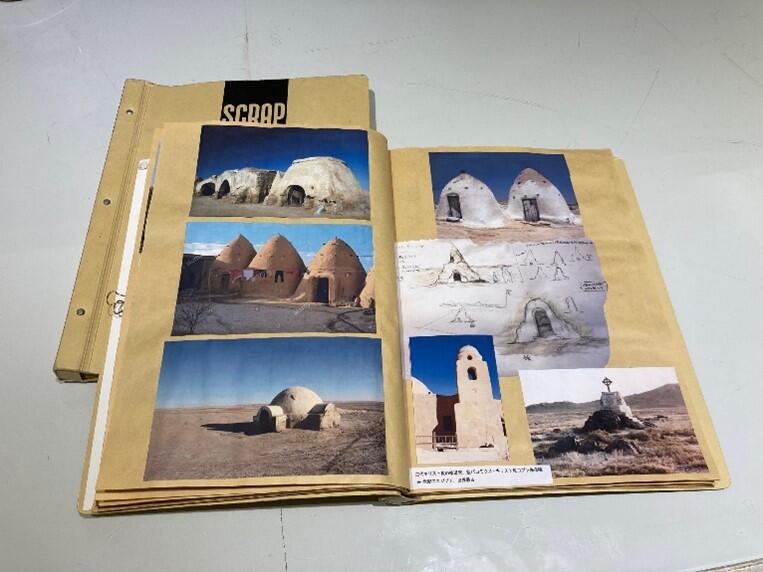

This work is Edition 7 and comes with a special box, so I hope you will enjoy it as well as the video.

"The Spirits of Cairn" special box attached to the video data

Special Box (detail)

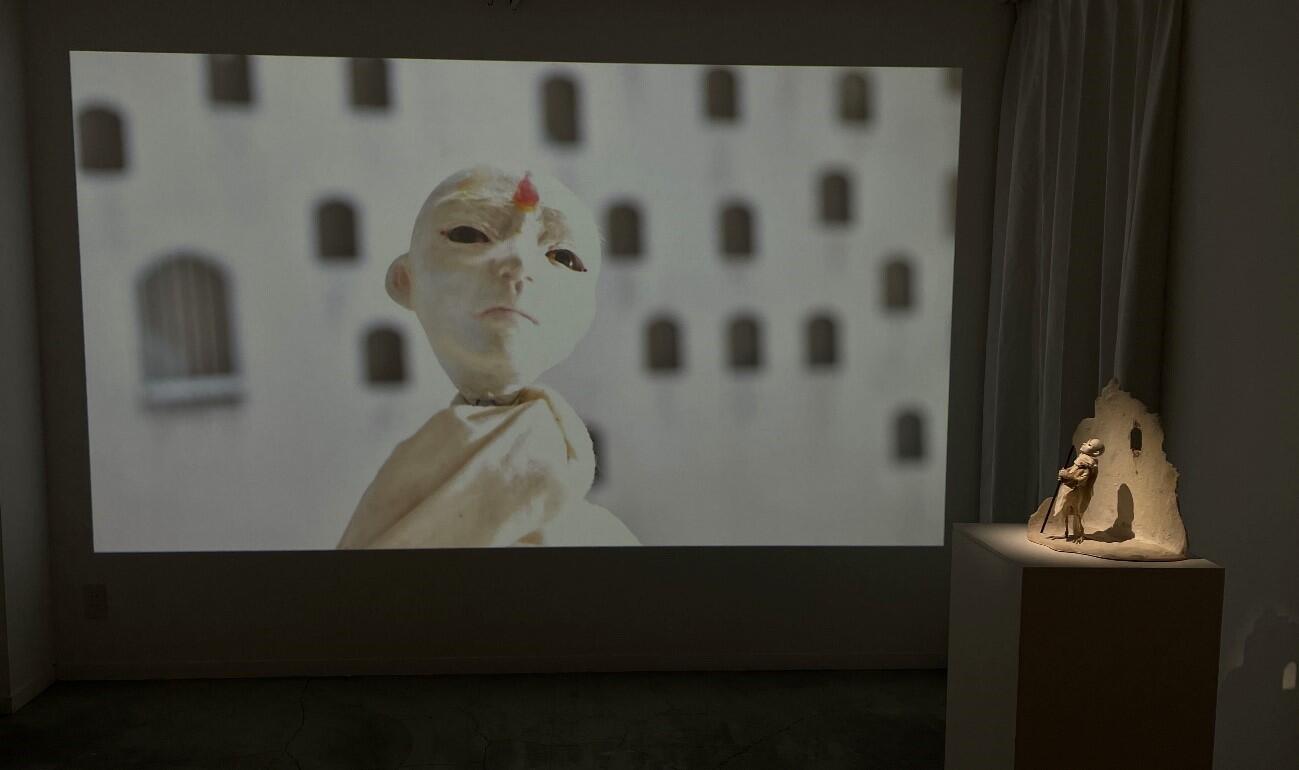

The next piece is titled "Blink in the Desert," which means "to blink in the desert". I wanted to use a poetic expression to describe the solitude of blinking in the desert with no one there to witness it, like the English phrase "needle in the haystack," which is like trying to find a needle in a haystack. The blink is a reference to the fluttering of wings of insects, the flickering of candlelight, and the fluttering of shadows and light, which I superimposed on the blinking of the protagonist's heart when it is in turmoil.

Deserts are believed to be places where neither gods nor humans exist, where there is no water, no vegetation, and where death comes to all of us. In the book "Monastery in the Desert," a Coptic monastery in Egypt is mentioned, and they go there to experience a temporary death.

To explain this work in a nutshell, the elephant is the righteousness, ethics, and light that the protagonist believes in, while the winged insect is a sudden negative emotion or a shadow that he wants to cover up. As in the previous work, I valued the tactile impact of dirtiness and breakage, but in this work, the physical "dirtiness" is directly related to the protagonist's inner dirtiness. It is similar to what is called "chi kare. Originally, kegare is something to be purified, but I originally took the method of giving life to the doll by the dirt itself, and I did not aim to purify it, but to allow the dirt received by the protagonist to accumulate, permeate, and stabilize, which is not to deny the dirt itself, but rather to make the dirt I set as the goal of the story the state in which the protagonist confronts the very nature of the dirt itself, not necessarily its kegels.

What is common in my works is that the objects that appear in my works bring about some kind of change in their modeling, such as something adhering to, staining, damaging, smearing, or changing shape, when they encounter other objects. For example, if a part of the material is transferred to the object, etc., traces of it accumulate, as if the boundary between the subject and the other object is fused. Or perhaps the fusion of the boundaries of matter, as if the protagonist's body and the outside world are gradually becoming one, is something like the decomposition of a bipolar structure, like subject and object, protagonist and outside world, spirit and body, human and world. Recently, I have been working with the idea that if a non-living entity could have a sense of life, it would be through such a material exchange.

《Blink in the Desert》2021 10min. 32sec. directed by Shinobu Soejima, Marty Hicks (music), Hisako Nakaoka, Nao Tawaratsumida (sound effect) Tokyo University of the Arts, Film & New Media (distribution)

The next piece is titled "Blink in the Desert," which means "to blink in the desert. I wanted to use a poetic expression to describe the solitude of blinking in the desert with no one there to witness it, like the English phrase "needle in the haystack" (like trying to find a needle in a haystack). I wanted to make it poetic, like the English phrase "needle in the haystack," which is like trying to find a needle in a haystack. The blink is a reference to the fluttering of wings of insects, the flickering of candlelight, and the fluttering of shadows and light, which I superimposed on the blinking of the protagonist's heart when it is in turmoil.

Deserts are believed to be places where neither gods nor humans exist, where there is no water, no vegetation, and where death comes to all of us. In the book "Monastery in the Desert," a Coptic monastery in Egypt is mentioned, and they go there to experience a temporary death.

To explain this work in a nutshell, the elephant is the righteousness, ethics, and light that the protagonist believes in, while the winged insect is a sudden negative emotion or a shadow that he wants to cover up. As in the previous work, I valued the tactile impact of dirtiness and breakage, but in this work, the physical "dirtiness" is directly related to the protagonist's inner dirtiness. It is similar to what is called "chi kare. Originally, kegare is something to be purified, but I originally took the method of giving life to the doll by the dirt itself, and I did not aim to purify it, but to allow the dirt received by the protagonist to accumulate, permeate, and stabilize, which is not to deny the dirt itself, but rather to make the dirt I set as the goal of the story the state in which the protagonist confronts the very nature of the dirt itself, not necessarily its kegels.

What is common in my works is that the objects that appear in my works bring about some kind of change in their modeling, such as something adhering to, staining, damaging, smearing, or changing shape, when they encounter other objects. For example, if a part of the material is transferred to the object, etc., traces of it accumulate, as if the boundary between the subject and the other object is fused. Or perhaps the fusion of the boundaries of matter, as if the protagonist's body and the outside world are gradually becoming one, is something like the decomposition of a bipolar structure, like subject and object, protagonist and outside world, spirit and body, human and world. Recently, I have been working with the idea that if a non-living entity could have a sense of life, it would be through such a material exchange.

G: How long does the production take?

S:Of all the processes, the scenario takes the longest. It takes about six months to a year to think about the story and examine it, 2-3 months to create the sets and puppets, 3-4 months for shooting, and 1 month for post-production. Once the scenario is decided, I can move pretty quickly. Basically, I make everything myself. Before making animation, I had been making three-dimensional works for a long time. I often gave narrative to my works, and I was interested in the phenomenon itself, such as the shape change of materials over time or their breakdown. I honestly thought that if I were to create something in three dimensions and give a story to the process art aspect of the work, what I could create by discarding and selecting would be three-dimensional animation, and to be honest, I had no interest in miniatures at first, but when I tried it out, it fit my physical capabilities, and from there I started animation.

G: What is your outlook for the future?

S: The work I am working on for this summer is a little different from what I have done in the past. Rather than having one main character and depicting him emotionally, I have the idea that our bodies are connected to the outside world, and for example, our internal organs may become the internal organs of others. For example, one's internal organs may become another person's internal organs. We eat plants born from the soil, expel them, return them to the soil, and eat what is born there again. I would like to consider the blurring of these boundaries in the way the world is presented.

With my past works, I had a clear trigger (having experienced the death of a young person), so I used that experience as the basis for creating scenarios, but with the work I am creating now, I think I am starting from an image, or rather, I am delving into what I can capture from this image. I think the work I am making now is a process of digging deeper into what I can capture from this image.

Please come and see Shinobu Soejima's work, in which she reexamines herself in the images.

Dystopia: Transition of Memory" will be on view through Sunday, March 5.